History

Students of the Red Cross Institute of the Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health, along with school founder Dr. Henry H. Hibbs Jr., stand at the Virginia State Capitol in 1918. (Credit: VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project/Special Collections and Archives)

Our beginnings: Historical context

In the early 20th century, Richmond, Virginia, was a modest-sized city rapidly developing into a large, urban landscape. The 1910 United States census showed over 127,000 city inhabitants, and that number continued to rise throughout the 1910s.

The city’s growth, however, also exposed several alarming developments in housing and sanitation, and numerous debilitating medical conditions brought on by a lack of resources. The 1913 “Report on Housing and Living Conditions in the Neglected Sections of Richmond, Virginia,” a housing and sanitation survey and likely the first of its kind for the area, was conducted by Richmond’s civic leaders interested in improving the welfare of the city community. The survey took 18 months to complete, including physical land surveys, interviewing community members and meeting with city officials on current building codes and regulations. In 1905, the population density of Richmond was 22 people per acre, making it the most congested city in the South.

The survey concluded that many homes within the city proper lacked indoor plumbing, and several properties backed up to neighborhood dumps. When it rained, contaminated runoff water flowed into wells, down streets and occasionally into homes. Many homes lacked proper insulation, it noted, which offered little protection from the outdoor elements. Furthermore, some inhabitants resided in one or two rooms of otherwise condemned homes, where the floors and/or roofs were rapidly deteriorating. The report also described how Shockoe Creek, which flowed through several sections of tenement housing and was considered a primary drinking water supply, had become so polluted “by the contents of several public sewers and the refuse from many slaughterhouses emptying into it” that the water was deemed highly toxic and unable to sustain life. After heavy rains, the creek would flood, and homes near the creek became submerged in this dangerous water for days at a time, sickening the residents.

Additionally, the survey demonstrated that communicable and noncommunicable diseases were rising, and many ailments far exceeded the national average. Richmond, at this time, had the second-highest mortality rate of all 50 leading cities in the United States, demonstrating a need for reforms in housing, building codes, sanitation and public medical education.

|

Disease Type |

Richmond Population Affected |

National Average |

|

Typhoid Fever |

17.8% |

20.0% |

|

Measles |

8.5% |

10.2% |

|

Whooping Cough |

31.7% |

10.9% |

|

Influenza |

17.8% |

11.0% |

|

Tuberculosis (all forms) |

250.6% |

177.9% |

|

Cancer |

87.4% |

81.3% |

|

Meningitis |

10.8% |

13.3% |

|

Cerebral Hemorrhage |

147.7% |

73.1% |

|

Heart Disease |

170.9% |

147.9% |

|

Pneumonia |

158.6% |

157.5% |

|

Nephritis, Bright’s Disease |

193.4% |

116.2% |

|

Violent Deaths |

114.5% |

95.7% |

Table information sampled from 1913 report “Report on Housing and Living Conditions in the Neglected Sections of Richmond, Virginia."

From this report, coupled with the growing interest in civic and social reforms that were expanding throughout the nation, Richmond’s philanthropists and community leaders knew it wasn’t enough to alleviate these conditions through a single program or initiative. They understood that Richmond, and more broadly, the southern region, needed a highly skilled and dedicated workforce to enact meaningful change. Richmond’s middle-class women of this time, who benefited financially from the “New South” economy built on industrialization, were better educated and more prosperous than their predecessors and those in many smaller communities. With more leisure time available to dedicate to social reform and welfare, and a history of benevolence, they became the catalyst for many progressive reforms throughout the city.

In October 1916, the Virginia Bureau of Vocations – a training and workforce center for young women – appointed a committee of 20 to examine how social work in and about Richmond might aid the city and provide training for young women interested in the social work profession. The professionals and social reformers assigned to this committee included notables such as:

- Miss Virginia McKenney, Bureau of Vocations, chairwoman

- Mayor George Ainslie

- Dr. J.T. Mastin, State Board of Charities

- Justice J. Hoge Ricks, Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court

- Dr. James Buchanan, Associated Charities

- Father James Hannigan, Travelers’ Aid Society and St. Joseph’s Mission

- Mr. Wortley F. Rudd and Dr. James Smith, Medical College of Virginia

- Miss Orie Latham Hatcher, Virginia Bureau of Vocations

- Miss Agnes Randolph, Anti-Tuberculosis League

- Dean May Lansfield Keller, Westhampton College for Women

- Miss Nannie V. Minor, Instructive Visiting Nurses’ Association

- Miss Katherine H. Hawes, YWCA

The resulting committee report explained that there was a significant need for social workers trained in the South who understood Southern communities’ nuances and specific needs. The committee believed that Southern communities were better served by Southern social workers, especially when anti-Northern sentiment still ran high within the community and region. Dr. J.J. Scherer, the future president of the school board, argued that “bringing trained workers to the South ‘from the Eastern schools’ did not solve the region’s problems [...] ‘however capable or well trained.’ ”

Furthermore, he explained that social workers from outside the South automatically had a serious disadvantage due to “ignorance of the local conditions and local ways of doing things.” Scherer’s declarations, along with the committee’s resolve for quality training for local women of the South, cemented the plans for the establishment of the Richmond School of Social Economy.

“Plans for the Richmond School of Social Economy, a training school for social work, to be organized immediately and opened March 1 (1917), were adopted yesterday afternoon at a conference on training for social work,” announced an article in the December 1916 Richmond Times-Dispatch. Furthermore, the article specified that “courses will be offered in the general subjects of social relief and family work, child welfare...public health and medical social service.”

Additionally, the school offered practical fieldwork in various social service organizations throughout the city under the direction of Richmond’s expert social work leaders. The first term was slated to begin on March 1, 1917, and end on June 1, 1917, with two years of study for program completion.

On April 17, 1917, the Richmond School of Social Economy incorporated with the following board of directors, three of whom were members of the original planning committee:

- Mr. J.J. Scherer, Jr. – President

- Mr. Wortley F. Rudd – Vice President

- Miss Virginia S. McKenney – Secretary

- Mr. F.B. Dunford – Treasurer

The board quickly realized that the school could not open in March 1917. With the school’s bank balance having shrunk to $400, they lacked funds for renting a learning space, textbooks and furniture. In addition, equally important as furniture and books, the school still needed a full-time director who would also serve as the only paid full-time professor in the beginning.

In June 1917, the board hired Henry H. Hibbs Jr., Ph.D., a 30-year-old enthusiastic social worker with an acumen for business, as director of the school with an annual salary of $2,000 when it was available. Hibbs, a Kentucky native, earned his doctorate from Columbia University in 1916 with a dissertation titled “Infant Mortality: Its Relations to Social and Industrial Conditions.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch quoted Hibbs, upon his arrival, as stating that Richmond offered the best location for the establishment of a social work school, as a social work school’s success rested upon being located “in the community where social work is well done.”

Immediately following his arrival, he was tasked with establishing a suitable location for classes and fundraising. He connected with John Hirshberg, the chairman of the administrative board for the City of Richmond, who oversaw all the city’s properties. The chairman indicated the city had a vacant third-floor space, directly above the two floors of the Richmond Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court, 1112 Capitol St., in downtown Richmond. (The location is now home to the Library of Virginia.) Hirshberg offered the space to the school for free. The floor consisted of three small rooms, all heated with wood stoves, had no electricity and required Hibbs to set up his office on the stairwell landing. Hibbs purchased secondhand furniture from auction houses on Broad Street. Invoices for these purchases show that straight-back chairs cost $1 each, an office chair was purchased for $4.75 and a typing desk cost $8. The school did buy 30 new, inexpensive and cheaply made tablet-arm chairs. Ever so generous with city property, Hirshberg gave the school a large table held in city surplus.

With a director and a location in place, the Richmond School of Social Economy opened its doors in October 1917, serving three primary goals:

- Training public health nurses

- Training social workers

- Training in emergency courses in Red Cross or civilian relief work and other forms of emergency social work at home

Thirty students registered for the first semester: seven in social work and 23 in public health nursing. The school set an annual tuition rate of $40 for its Social Work and Public Health courses and $20 per semester for Red Cross training.

The first student to enroll at the Richmond School of Social Economy was Miss Mary Dupuy. Dupuy, in recalling her first impressions of the school and Dr. Hibbs, wrote years later, “I followed the winding stair to the third floor and found three former bedrooms, one little larger than a closet. There were no electric lights, but each room was lighted by gas. The two larger rooms had wood-burning stoves for heating.” Upon her arrival, Miss Lou Mayo Brown, the school secretary, introduced her to Dr. Hibbs, “a be-spectacled and mustached young man who gave me a highly cordial welcome. Answers fell readily from his tongue [...] so eloquent I enrolled as a student before I left.”

From its earliest days of formation, the school leaders began developing partnerships with local public and private organizations – groups that could lend insight into curriculum development and instruction and provide a range of hands-on environments in which students could work and learn. For example, the 1917-1918 school bulletin explained that “the new School exists by the cooperation of many philanthropic agencies, which have assisted in working out the courses best adapted to their own need for trained social workers.” These partnerships allowed part-time, unpaid lecturer positions that enhanced the coursework with informative and real-time social work experiences. The first lecturers at the school included notable Richmonders such as:

- Miss Loomis Logan, assistant in Office of Children’s Home Society

- Richard Messer, sanitary engineer, State Board of Health

- Miss Nannie J. Minor, superintendent, Visiting Nurses Association

- Ms. Agnes D. Randolph, executive secretary, Anti-Tuberculosis Association of Virginia

- J. Hoge Ricks, judge, Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court of Richmond

- Miss Jane B. Ranson, A.B., R.N., state supervisor, Public Health Nursing

- Ernest Lee Ackiss, A.M., assistant professor of English Bible, Richmond College

- Mary Lancaster Smith, director, Domestic Science Department of Y.M.C.A., Richmond

- Roy K. Flanigan, M.D., chief health officer of Richmond

- Leroy Hodges, A.B., secretary, Virginia Commission on Economy and Efficiency

- Dr. Ennion G. Williams, M.D., state commissioner of health

- Dr. William Higgins, psychological examiner, City Schools, Richmond

After the school year commenced, Hibbs focused on the challenges of fundraising and continued school expansion. As World War I in Europe grew, many of America’s rural physicians were drafted or registered to travel overseas to aid the military. Within the first month of the school’s opening, Hibbs received a war draft. The United States secretary of war expressed a sincere interest in aligning the War Department with the school and assigned Hibbs to service that allowed him to remain in Richmond.

Early in his collegiate career, Hibbs had attended the Boston School for Social Workers. Due to this background, the secretary of war believed that under Hibbs’ leadership, the school could successfully operate an American Red Cross training program that educated women on administering to the families of military personnel. This group of trainees was named Red Cross Home Service workers, and in its first year, the Richmond School of Social Economy enrolled 24 students.

Hibbs also recognized that if the school expanded to offer short courses of four months that could train nurses to render medical care while doctors were overseas, it would aid in raising additional capital. He coined the campaign slogan “To train public health nurses to take doctor’s places” for the fundraising efforts, and Richmond-area businesses quickly invested in the school’s ongoing efforts. Hibbs, years later, wrote that he realized no new agency or business “could live during a war unless the organizers could clearly show that it contributed to the war effort” and tailored the educational offerings to make the necessary contributions.

These additional educational programs meant the school needed a name that better reflected its mission. So, in early 1918, its board voted on a name change – The Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health.

In June 1918, 43 students graduated from The Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health, and enrollment had swelled to almost 100 (across all of the full-time and part-time programs), far exceeding the goals set by the board. In addition, a July 1918 newspaper article noted that school graduates came from Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and West Virginia, proving that a Southern social work school was much needed and appreciated.

In 1919, the school added a specialization program in recreation, which taught community leaders the importance of developing play spaces for children and offered officials an opportunity to teach proper hygiene to youngsters. Miss Claire McCarthy, an official with the city playgrounds board, became the first enrolled student of this program. She recalled that “the recreation and playground course was very practical. I was able to put the first instruction into immediate effect.”

Also, in 1920, the school contracted with the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, to offer extension courses during the afternoon and evening hours at John Marshall High School. This affiliation made it possible for students enrolled in the social work, public health and recreational programs to obtain a four-year degree by attending two years of courses in Richmond and two years in Williamsburg.

Between 1923 and 1925, school enrollment increased, and Hibbs needed a much larger building for classes. The school moved to 17 North Fifth St., across from the Fifth Street YWCA. The YWCA generously offered the use of its gymnasium and cafeteria. Rent was $75 a month, and the school remained in this location for two years until it once again needed more room for expansion. According to Hibbs, by 1925, 37 full-time students and “several hundred” part-time night students were enrolled.

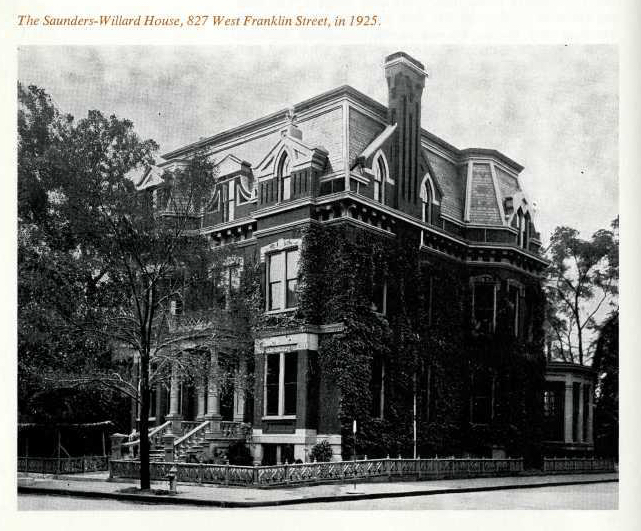

The school’s board of directors began engaging in dialogue with William & Mary’s president, J.A.C. Chandler, about “William and Mary taking over the school entirely.” Chairman John M. Miller Jr. of the finance committee indicated that the feasibility of soliciting funds each year from the community for the school’s continued operation seemed impossible. Miller hoped that an arrangement with an already state-supported school might secure state college funding for operations. Chandler agreed that William & Mary would take over the Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health on two conditions: 1) the school would secure a permanent home, preferably a property located at 827 West Franklin St., and 2) the school would raise $100,000 to go toward the purchase of the building and any necessary repairs.

827 West Franklin St., named the Saunders-Willard House – and now VCU’s Founder’s Hall – was a large three-story mansion with a sizable stable in the rear and a small, vacant lot on the east side. According to Hibbs, the home’s location brought some concern about it being “too near the business section” and that it “could never be made to look like a campus.” Others on the board felt that the excellent location might attract more tuition-paying students and allow for higher tuition charges. Additionally, its location across the street from the Richmond Public Library (at the time) provided students additional space for learning.

For the purchase of the building, the school initiated an aggressive fundraising campaign in March 1925. Students such as Miss Lila Spivey, Miss Lillian Gorton and Mrs. Bessie L. Woolfolk spoke to members of the Chamber of Commerce every other day, soliciting funds from local businesses. The school also assigned 10 teams with 10 members each to solicit community-based donations. Finally, on March 19, 1926, the board’s treasurer announced pledges that totaled $103,925, almost $4,000 more than the goal.

As a result, the property at 827 West Franklin St. was purchased for $73,000, and $23,000 in improvements were made to the building and its outbuildings. The Franklin Street location operated as classroom space and also as a dormitory for the school. In the first year on Franklin Street, the school’s full-time enrollment was 52 students and 393 part-time students. Four full-time faculty and four part-time instructors from William & Mary taught each of the programs offered, and the school became known as the Richmond Division of the College of William & Mary.

In 1939, the School of Social Work changed its requirements for admission. In years past, the conditions were a demonstrated maturity and an aptitude for working with people. However, during this time, social work schools across the country began requiring college graduation as part of their admissions process. In requiring a four-year degree, a more astute professionalization of the social work field arose. Courses in sociology, social science and recreational leadership were placed under the School of Applied Social Science, emphasizing the importance of professionalism. Dr. Hibbs explained that the use of the term “applied” was to “counteract the uneasiness of some liberal arts colleges which feared that ‘RPI (Richmond Professional Institute) was duplicating their work.’”

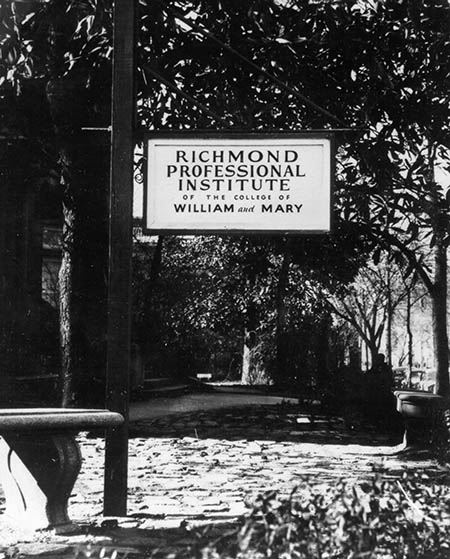

Also in 1939, the school changed its name – this time to the Richmond Professional Institute of the College of William and Mary. William and Mary’s president, John Stewart Bryan, explained the decision: “Since it is a specialized institution whose reputation depends not on work in arts and sciences but, mainly, on education of the occupation, technological or professional type, why not call it the ‘Richmond Professional Institute,’ with the abbreviated name of RPI?” As a result, enrollment growth at RPI flourished, and programs including and outside of social work expanded rapidly.

In the following decades, the school’s scope of influence grew to match its vision. By providing genuine and truly needed opportunities to the people of Virginia, the school eventually became VCU, helped to found the Council on Social Work Education, and evolved into one of the premier centers for social work education in the nation.

A timeline of our deans

- *Gary S. Cuddeback: 2023-

- Rebecca Gomez (interim dean): 2022-2023

- Beth Angell: 2018-2022

- Timothy Davey (interim dean): 2016-2018

- James Hinterlong: 2010-2016

- Ann Nichols-Casebolt (interim dean): 2008-2010

- Frank Baskind: 1992-2008

- Grace Harris: 1982-1991

- Elaine Rothenberg: 1972-1982

- Richard Lodge: 1966-1972

- George Kalif: 1943-1966

- Henry Coe Lanpher: 1940-1943

- Henry Horace Hibbs Jr. (founder of Richmond School of Social Economy): 1917-1940

*Dr. Cuddeback was appointed dean Oct. 28, 2024, after serving as interim dean from July 1, 2023.

Historical highlights

Henry H. Hibbs Jr., Ph.D., joins the Richmond School of Social Economy as the director. The first session begins in October. Classes are held in three small rooms on the third floor of 1112 Capitol St., across from the governor’s mansion. The requirements for admission included “maturity for age and an aptitude for working with people,” as many other social work schools required at the time. (Photo credit: VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project/Special Collections and Archives)

- Mrs. Bessie A. Haases joins as the second full-time faculty member, teaching public health.

- The school changes its name to the Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health to better reflect the educational opportunities offered by the addition of the public health program.

- The school quickly outgrows its Capitol Street location and moves to 1228 Broad St., a building owned and provided rent-free by Monumental Church.

- As one of eight charter members, the Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health founds the American Association of Social Work. This organization helps to set professional standards for social work education throughout the United States. In 1952, it would amalgamate with the National Association of Schools of Social Work, a competing social work organization, to establish a single social work professionalization entity – the Council on Social Work Education.

The school is affiliated with the Extension Division of the College of William & Mary, enabling students to earn a bachelor’s degree. Under this agreement, the first two years of the social work program are completed at William & Mary and the last two years in Richmond. Majors included social casework and community social work.

- Mrs. Roy K. Flanagan, an ardent supporter of the school, starts the first alumnae association.

- The school moves from Monumental Church to 17 North 5th St., as it needs more space for teaching.

The school purchases its first building, the Saunders-Willard House, located at 827 West Franklin St., which provided dormitory and classroom space. The purchase also included an adjoining vacant lot and a rear stable. The building is now known as VCU’s Founder’s Hall.

- The school purchases a Ford Model T to reach rural communities with social and public health fieldwork. Student Miss Byrd McGavock recalls from her use of the vehicle that “the only protection riders had from the weather were old, worn-out curtains...but we went out every day regardless of the weather.”

- The College of William & Mary assumes control over The Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health and renames it the Richmond Division of the College of William & Mary.

- The school becomes the Richmond Professional Institute of the College of William & Mary, combining the Richmond School of Art, the School of Store Services Education and the college’s vocational departments into a cohesive unit.

- The School of Social Work transforms into a graduate program. It requires college graduation as part of the admission requirements; previously, applicants only needed to be of appropriate age and have a desire to become a social worker.

Director Henry Coe Lanpher announces that a recent survey indicates that 55% of social workers employed by the Commonwealth of Virginia and 41% of those employed by the 124 local government units were trained through the Richmond School of Social Work.

The Richmond School of Social Work collaborates with the Departments of Health Education, Recreation and Physiotherapy to develop an Emergency Defense Program in response to World War II. The program offers courses from each area designed to prepare students for wartime work.

The school moves to a three-story house at 812 Park Ave.

The school reorganizes its curriculum in the face of substantial social change, implementing courses in research, human growth and development, social welfare policies and services, practice methods, and supervised fieldwork. Over the next decade, it also will add social group work, community organization and social work administration courses to the curriculum.

In July, the General Assembly votes to combine the resources of the Richmond Professional Institute with the Medical College of Virginia to create Virginia Commonwealth University.

The school introduces the first of a growing number of interdisciplinary options through a partnership with the Presbyterian School of Christian Education. Over the decade and beyond, these offerings have grown to include a school social worker certification program, a dual-degree program with the T.C. Williams Law School at the University of Richmond, and a combined M.S.W. and Certificate of Aging Studies program.

The advanced standing program, in which B.S.W. degree-holders can complete an M.S.W. degree in one summer semester and one full academic year, is developed to accommodate large classes and students who want to receive credit for previous training. Students immediately gravitate toward this program and expanded course time options and evening classes — all efforts to offer a wide array of options for growing student needs.

The doctoral program is established, making VCU one of the few schools in the nation to offer bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral levels of social work education.

Alumna and professor Grace E. Harris, Ph.D., one of the first African American faculty members hired by VCU in 1967, accepts deanship of VCU's School of Social Work in 1982, where she would serve in the role for nine years.

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) holds its annual meeting at VCU, in conjunction with the School of Social Work.

The School of Social Work celebrates its 75th anniversary.

The school offers its first course via distance-learning technology.

- The school hosts the first “Social Justice Week” in March. Topics discussed in the programs include equal access among individuals who need social services, poverty and equality, and violence against women.

- The school is awarded a federal contract to administer the Richmond Head Start Program in community agencies. It would manage this program for the next decade.

The school collaborates with Habitat for Humanity to build a home for a Richmond family as part of a service learning project. So many students want to participate in this popular event that, unfortunately, some have to be turned away.

The Mayor of the City of Richmond officially proclaims the week of March 21-28 as “Social Justice Week.”

Students and faculty members volunteer annually to perform community work in the Dominican Republic. Projects include building a local school and providing basic medical care.

- The school’s “Social Justice Day” honors the life of renowned civil rights lawyer Oliver W. Hill, who had a significant role in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown vs. The Board of Education. Hill attends the event, where the school presents his awareness organization, Evolution Change Foundation, a $1,000 check.

- The school co-sponsors “World Food Day” with the Department of Urban Studies and Planning/Geography Program. The 1998 Nobel prize winner in economics, Amartya Sen, speaks at the event on “Poverty and Hunger: The Tragic Link.”

The first students graduate from the school with the M.S.W./M.Div. dual degree and the Certificate in Nonprofit Management.

Students and faculty travel to Ghana over winter breaks to participate in weekly feeding and educational programs and to administer basic medical aid to children in various areas of the region.

- The Master of Social Work Program develops the school’s first international field placement in the Dominican Republic.

- In collaboration with the VCU School of Education and the Virginia Literacy Foundation, the social work-led Head Start program implements the Richmond Early Reading First (RERF) Program. In addition, in collaboration with the Partnership for People with Disabilities and the Department of Occupational Therapy, they implement a Sensory Integration Project for children in its community programs.

The school’s Head Start Program addresses childhood obesity by introducing “I Am Moving, I Am Learning.” The Head Start National Reporting Instrument assessment scores place VCU Head Start children at or above the national average in testing domains.

- Faculty members participate in a university delegation to the University of West England, University College of Dublin, the University of Guadalajara and the University of Cordoba.

- The school delivers its first formal continuing education series as a unit of community engagement.

- Faculty and students contribute research and commit to supporting central activities for the For Keeps Initiative, a multifaceted effort to improve outcomes for older children in Virginia’s foster care system.

Construction on the school’s new facility, and current location, begins on Floyd Avenue. This building is named the Academic Learning Commons and is four floors high, with state-of-the-art classrooms on the first and second floors.

The school moves into its new space inside the Academic Learning Commons, which expands school space by 50% and allows for a Student Success Center.

School members develop Richmond [Re]visited in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. This annual program examines the long and troubled history of slavery, segregation, discrimination and racism that permeates Richmond’s communities. The daylong event includes visits to neighborhoods and other significant locations around the area affected by racism and lectures by scholars, activists and social work professionals at these locations. Social work students learn the root causes of issues such as structural racism and social oppression through a racial justice lens.

- The school celebrates its 100th anniversary with a yearlong celebration of activities and events. On Oct. 4, 2017, the school commemorates its founding with the unveiling of a Virginia Department of Historic Resources highway marker that acknowledges the founding of Richmond Professional Institute.

- Additionally, emeriti faculty members Florence (Flossie) Segal, Jaclyn Miller, Renate Forssmann-Falck (widow of the late Hans S. Falck) and David Fauri are honored with an unveiling of a plaque celebrating their service to the university as past presidents of the Faculty Senate.

The school launches its Master of Social Work Program in a fully online format that allows students from across the nation to join the VCU social work “RAMily.”

- The school creates the Pay It Forward Fund to assist currently enrolled VCU Social Work students who encounter an unforeseen financial hardship that would prevent them from continuing their education. This fund has aided many students with continuing their education and their pursuit of becoming social workers.

- The school establishes RAACE (the Radical Alliance for Anti-Racism, Change, and Equity) task force, which brings together faculty, staff, students and alumni to guide the school in self-reflection and action against systemic racism. School community members participate in open dialogue sessions and trainings and engage in critical conversations about diversity, equity and inclusion.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the school holds two outdoor Commencement ceremonies at Richmond’s City Stadium, graduating nearly 300 mask-wearing B.S.W. and M.S.W. students. Several hundred guests also attend.

Rebecca Gomez, Ph.D., LCSW, is named interim dean, effective May 2022.

Gary S. Cuddeback, Ph.D., is named interim dean, effective July 2023.

.JPG)